From the editor: More than a year ago, we lit out on a quest to make sense of the tremendous changes afoot in the West fueled by the pandemic, George Floyd’s murder, a rise in anti–Asian American and Pacific Islander violence, the #MeToo movement, dam removal, land back, and the fury of climate change, to name but a few significant events. We had sheaves of notes and ideas but quickly realized we’d need to tether our examination to the past; we’d need the West’s preeminent historian to guide us. Fortunately, he said yes.

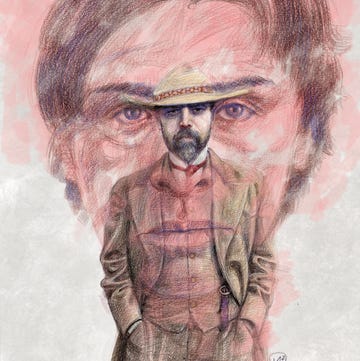

William Deverell, a longtime contributor to Alta Journal, is our first-ever guest editor. There is no one more qualified for the task, and from the moment he enthusiastically accepted this opportunity, Deverell has worked tirelessly on your behalf, recruiting historians, refining stories, and forcing us to consider reckoning in all its dimensions. Deverell is the founding director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and a professor of history at the University of Southern California. He’s the author of numerous books about the West, a recognized leader in his field, and, as this issue attests, endlessly creative and just plain brilliant. Enjoy.

—Blaise Zerega

It is a mile from my house to one that conjures for me an earlier reckoning with the American West. I have driven the short way on a number of occasions and eyeballed the odometer each time. I have recorded the distance on my phone’s step counter. That one mile separates my home from the house where the historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861–1932) lived in Pasadena after retiring from Harvard in the first third of the 20th century.

This is peculiar. Not only that it is true but that it means something to me. Some of this import is, I am sure, because of our shared membership in the western-

history world (a world in which Turner is famous). It is also due to the exactness of that mile, just about 2,100 steps each time I walk it. A “survey mile,” this can be called, as that’s the formal designation. Or a “statute mile.” Or just a single mile.

Who cares, really? A mile, a half mile, five miles, right next door, so what? I confess that it is nonetheless meaningful to me. Something about the act of measurement, a standard of measure, a sense of taking the measure of the West as I walk west to the former home of a scholar whose legacy is bound and bound up in the narrative and the meaning of the American West in U.S. history. My route invites its own miniature version of a reckoning with this region.

This article appears in Issue 29 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

The Turner home is a modest yellow bungalow. I often wonder whether the current residents know who lived there a century ago. While I’ve never lingered outside, I once took two historian friends by. They had come to the Huntington to work together in the voluminous Turner Papers, more than 300 boxes of his notes, lantern slides, correspondence, and writings. They had no idea that he’d once lived in Pasadena, and when I drove them to the bungalow and stopped out front, they were thrilled. “Really?” one of them asked me. “F.J.T.’s house?”

This is the last home of a scholar whose ideas about the American West tied three or more generations after him to his elegant, elegiac, and ultimately wrongheaded sense of how reckoning and the American West dovetailed.

Frederick Jackson Turner (“Fred” to friends and family, which feels jarring and incongruous to me) was one of the most influential American historians not only of his time but well beyond into ours. Like a mathematician or a gymnast, he arrived at the height of his powers early, virtually at the start of his career.

Such precociousness is unusual for a historian. We expect that decades of research, writing, and teaching add perspective, nuance, and simply a lot more compiled erudition in the work of our most esteemed scholar colleagues.

That’s not quite how it worked in Turner’s case. Trained in the nation’s earliest era of doctoral education, Turner did his most important work at barely 30 years old near the end of the 19th century. You probably know something of the story. A scholarly paper, delivered in 1893, catapulted the young Turner to the highest echelon of interpreters of the nation’s history. The paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” made a grand argument. Through generations of westering at the moving edge of “the frontier,” leaving behind all that lay east of it (cities, civilization, settled society), Americans reinvigorated democratic institutions and democracy itself. The frontier process and all that it entailed in terms of “taming” the West was, Turner argued, the engine of what Americans would come to call “Manifest Destiny,” which ensured the ongoing fitness of the republic. As long as there existed an open western frontier, to both escape to and wrestle into submission, the nation would be assured of democratic health and well-being. The elegance of the theory lay in Turner’s implicitly congratulatory understanding of what American settlers accomplished: go west, young men and young women, carrying with you the spirit of democracy and its institutions.

With that paper and its subsequent publication, Turner’s famed Frontier Thesis (or just Turner’s Thesis) was born. In only 7,000 words, the essay sought to explain the impact of the West to the nation across hundreds of years of frontiering. Each generation moved west—generally a couple of miles at a time, sometimes more (as in the gold rush, when exuberant miners played leapfrog across the western half of the continent in their race to the California goldfields). Successive western emigrants encountered and surmounted obstacles and, in so doing, nurtured the nation. The West and the moving frontier (across the Alleghenies, across the plains, across the Rockies, across the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada) were, Turner and his thesis claimed, the sine qua non of the health of the republic. It was true, the thesis claimed, in 1790 or 1810, 1830 or 1850. All that unidirectional east-to-west frontiering fed the new nation and kept it alive through early years of political and other vulnerabilities.

Part of what Turner was doing was getting the measure of the West and its scale. Some of the region’s “significance” came simply by way of its sheer size. The young scholar’s extraordinarily influential, even revolutionary, reckoning with the West came just a few decades after territorial acquisition at the grandest scale. Turner had that scope in mind when he formulated his ideas, and he found a way to marry the extent of the West with an argument about its profound influence.

People who these days bicycle across the West, and surely those hardy souls who walk it, inevitably grasp its scale. It’s harder to do so in a car, but an airplane window seat on a clear-day flight from, say, Boston to San Francisco offers up some sense. Nonetheless, I think we have mostly forgotten and rarely acknowledge the magnitude of what (and where) “the West” was by the middle of the 19th century, when hundreds of thousands of people walked to it from parts east looking for land and gold. The West, to most of us, just is, though we know that there’s a history to this becoming. The velocity and significance of that change, the weight of the West upon national character, is in part what Turner grappled with, as do, in far different ways and approaches, the writers featured here in this special issue of Alta. It was once fashionable to ask “how the West was won.” Now, it’s far more illuminating to inquire “how the West was” and to use our interpretations to better understand life in the dynamic region today.

In his magisterial new book, Continental Reckoning: The American West in the Age of Expansion, the historian Elliott West posits a brilliant way to capture that conjunction of velocity and region in reference to a span of barely two years not long before Turner’s 1861 birth. “Between February 19, 1846, and July 4, 1848,” West writes, “the United States acquired more than 1.2 million square miles of land. It was far and away the greatest expansion in the nation’s history, more than half again what had been added in the Louisiana Purchase more than four decades earlier. Should the nation add that much today, expanding not to the west but to the south, our borders would embrace all of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama, and more than half of Colombia.” This is remarkable (and so clever to measure expansion in this way).

These newly conquered square miles were all in the American West. Taken together, they immediately yanked the nation, from whatever or wherever constituted “the East,” to and beyond the Rockies and the Great Basin; greatly expanded the borderlands; and came to full length on the shores of the Pacific. What had once been the West—the Old Northwest that lay west of Pennsylvania, the Old Southwest of states and territories east of the Mississippi and south of the Ohio River, and what we now call the Midwest—gave way to this new West.

Americans, as well as immigrants from everywhere on Earth, reckoned with all that land and with who and what dwelled on it. Make no mistake. Coming to terms with the West, for Turner’s unnamed sea of western pioneers, relied on violence. The territorial smash-and-grab of war and manifest destiny strengthened the zeal of all those hundreds of thousands of supposedly small-d-democratic settlers busy chopping down forests, killing or corralling Indigenous peoples, wiping out the bison and the otters and the beavers, and defiling the rivers, streams, and mountainsides with mining and irrigation enterprises. Turner implicitly celebrated all this; subjugation of the West and its people was a process that, viewed through Turner’s interpretive prism, yielded positive results for the nation.

We no longer perceive things this way, at all. Our reckoning with the West hews more closely to bereavement than celebration, and you will detect that in these pages. We see a melancholy dance between the West, grief, and the possibility of redemption or atonement. The reckoning of an earlier time had blinders on when it came to loss. Surmounting obstacles, even if those obstacles came in the form of Indigenous human beings, carried with it assumptions (and then declarations) of triumph. Running parallel to these beliefs was an unquestioned faith in the new West’s limitless size, resources, and opportunities. Little wonder that loss did not much figure into the ways the West was seen and assaulted.

That faith would be quaint and naïve if not for all the blood and the violence and the destruction. Look to the figures presented throughout this issue by the geologist Ruby McConnell, some of which take the arithmetic measure of the American West in the era of manifest destiny. Such earlier, quantified reckonings of the West went hand in hand with a catastrophic understanding of the West. Those who took all those measurements—of acreage, of timber, of mineral wealth, of just about anything—did so in part because they reckoned that vast quantities actually meant everlasting quantities. They were right in the first instance (vastness) and wrong in the second (without end).

This Reckoning with the West Issue is our collective project of getting heads, arms, and hearts around this place through words and images. What is that seam between the past and the present? Where and how do they meet, and on what terms? Where do we go from here? Split between three themes—people, land, and culture—this issue moves broadly through and across western time and space. Presenting different ways of tackling the region, the parts also—inevitably—speak to one another. All of us who put this edition of Alta together believe that a better future can be built upon a new cultural foundation that reimagines and rediscovers truths of the western past.

I walk that clean mile to Turner’s home and think of the irony. Only a few decades after the heyday of imperial western exploration, after the mapmaking, the science, the promoters, the settlers, the railroads, and the politicians had reckoned on unending abundance, along came that thirtysomething historian saying something very different. Something had run its course, Turner declared. Something in the West had actually run out. The frontier had closed. It ended with the reckoning born of the 1890 federal census. In that report’s scatterplot demographic illustrations, Turner could no longer discern an unbroken longitudinal line between settlement in the East and frontier landscapes in the West.

With that closure, in Turner’s famous formulation, “four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.” That was a bold claim about both what the West had been and what this “closing” would mean as the 20th century beckoned. What would the nation do, what would it be, without its western engine of democratic renewal?

Turner grossly misread the genocide and environmental destruction of the frontier era. He had a unidirectional conceptual and geographic map, east to west. There was no grappling with south to north, no room for west to east, no room for immigrants coming across the Pacific, as so many did, willingly or otherwise. The thesis erased all the complexities of migration and immigration that did not, to Turner, look like western expansion.

What he wondered was whether the new 20th century, which he knew would be the century of the American city (where so many of the children and grandchildren of the frontier would go), could find tools and processes to carry on the democratizing work that he believed was supplied on the frontier.

We appropriately rebuke Turner, dead now for nearly a century, for missing so much darkness surrounding all that western frontiering. For Turner, the West’s great forests were the proving grounds of democratic stability. Our contributors to this issue see other things, foreboding things, in those settings.

How might, how can, redemption and region run together? Hopeful prospects peek out from these pages and these essays. Lynell George is typically thoughtful in her essay on the Destination Crenshaw project. Designed to honor the history and vibrancy of the Black community in Los Angeles, the intricate, expensive, and complicated effort has become a case study of promise and pitfall. Redevelopment for the future and reparation for the past can embrace, but no one should doubt the ferocity of the challenges.

Keri Blakinger’s edgy tribute to Los Angeles has no fan fervor, no hyperbole, no breathless adjectives about the city she now calls home. Equally honest is Eugene S. Robinson. Worn out by crime, natural disasters, and a high cost of living, he writes a long goodbye to the region after four decades of adventure. For Blakinger and Robinson, the vast L.A. metropolis and a Spanish hillside, respectively, just might nurture seeds of personal redemption.

I feel similarly about novelist Karen Tei Yamashita’s haunting consideration of human histories enacted in a sparse landscape in Utah. She walks with ghosts. They speak to her, and she speaks to us through them.

Katie Hickman walks west with the evangelizing pioneers of nearly 200 years ago. In those landscapes where wagon ruts of the Oregon Trail are still visible, she finds a kind of fleeting connection to Narcissa Whitman—a woman who wrapped her faith with courage on an eventually tragic journey into the deep unknown of the far West. It’s the land itself that helps Hickman travel through time, a reminder that any journey to the western past will be enhanced by periods spent in situ. Western ghosts come in all forms: people and trees, bears and wagon roads.

Joshua Wheeler delivers cultural insights about the nation and the West in his journey with one representative member of the Ursus americanus species. In his moving essay, Wheeler makes a pilgrimage to the grave site of a fellow New Mexican. He goes there to grieve, to fold blame with bereavement, to ponder and reckon with loss.

Likewise walking with sorrow, Christopher Hawthorne laments that our western memorials and those who make them cannot keep up with the demand; Hawthorne’s essay is at once a critic’s take on design and execution and a reckoning with the lost, the forgotten, and the murdered that is heavily laden with anticipatory mourning.

We cannot mend the western past. It is unalterable: whatever happened, happened. It cannot be fixed; it cannot be repaired. All we can do is rework our sense of that past with the tools of history. Mending, repairing, revisioning, unraveling: these are critical verbs, all of them kin to reckoning. So we examine murals with new eyes; we look anew to memorials and commemorations. Let us mourn the slave marts of the Old West and the sites of massacres. But let’s also go to the places of these horrors. Perhaps you’ll find in these pages a meaningful guidebook to the West we all share, one that does not shy from pain?

When I hold this edition of Alta in my hand, with all these thoughtful pieces about the meanings of western people, western lands, and western cultures, I’ll walk over to Frederick Jackson Turner’s house again. And when I do, it’ll be with all these very recent reckonings of all these talented writers in mind. Reckonings of western loss, yes. But also reckonings about taking measure, of searching for meaning in the measuring. This is an era, and these are viewpoints, built on far more acuity regarding grief and loss. With such clear-eyed acknowledgment of this region’s history, we must put faith in the power of historical perspective to enhance our protest and our future.

Isn’t that what reckoning means? I can measure—I can reckon with—those 2,100 steps between my present West and Turner’s earlier West. But the power of reckoning goes far beyond metrics of space. It’s the realm of time where the payoff really comes. That mile between my home and Turner’s yellow bungalow feels strangely comforting to me; it asks what the West means now and what it will mean tomorrow. I’d take my West of 2024 over his any day.

The past is behind us. History is not.•

William Deverell is the co-director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and a professor of history at USC. He is also the founding director of the USC Libraries Collections Convergence Initiative. He is a historian of the 19th- and 20th-century American West. His undergraduate degree in American studies is from Stanford, and his MA and PhD degrees in American history are from Princeton. He has published widely on the environmental, social, cultural, and political history of the West.