When The Monkey Wrench Gang was first published in 1975, Ed Abbey gave me a signed copy that read, “To Douglas who is the hero of this here book.” Although I had previously skimmed the unedited manuscript for “technical editing,” as Ed had requested, I devoured that fresh novel during a tiny handful of desert nights. It was a hoot.

While you can still read it for the laughs, the novel has endured because of its deeper themes of resistance: the overarching notion of questioning authority and using select sabotage to defend the wilderness. The book is still considered one of the more influential in the history of the modern conservation movement. Some see it as the most important, especially among the more militant Western groups.

Beyond the fun, the chase scenes, and the action—blowing up a railroad bridge and derailing a train—we find a book whose larger message hits us smack in the face in these troubled days, informing modern generations how we might act and live in a burning world on the edge of war. It was Ed who pointed out the insanity of believing we could have endless commercial progress on a planet of finite resources, a conceit that is still driving us, as it did 50 years ago. Therein lies his lasting value to all of us.

This article appears in Issue 32 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

I first met Ed in the winter of 1968 at Bill Eastlake’s house in rural Tucson. It was cold, and I had covered the distance between my house and Bill’s on my motorcycle. I cautiously knocked at the door. Inside, a number of people sat around the room, mostly men, possibly writer types. I took a seat on a bench next to a rangy man with a dark beard. I smoked cigarettes then, so I took a plastic bag of Bugler tobacco out of my pocket and rolled a joint-like smoke. Grabbing a match, I tried to light it, but the cold had caused my hands to tremble. The man next to me reached over with a lighter. His name was Edward Abbey.

Ed and I talked into the night, discussing mountain lions, about which he would eventually write for Life magazine. Ed worked as a seasonal ranger for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument down in the southwest corner of Arizona. He said, “Come on over and visit.”

So I did, hauling with me a bottle of whiskey and a six-pack of Mexican beer, which is how you visited new friends in those days. (Ed had previously knocked on the door of Bill Eastlake’s remote ranch in New Mexico apprehensively clutching a bottle of cheap gin.)

Ed bunked in a National Park Service Quonset hut down the road from Bill, near Mexico. We drank and talked late into the night, very late for a working man. He directed me to a couple of natural springs in the monument, as the low Sonoran Desert was relatively new to me. Ed pointed out that Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, though a lush and diverse desert habitat, was tame when compared with the adjacent Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge to the west, a land of wild and empty valleys, no roads or people—where Ed and I would take our final trip 20 years later.

Starting in about 1969, I would see Ed regularly at Bill’s, or him and Bill at the home of Alan Harrington, another Tucson writer. I was still reeling from my years in Vietnam. At 27, I had no road map for reentering society and no impulse for reform. Though estranged from my own generation, I wasn’t lost: I had glimpsed those wild landscapes up in grizzly country and again in the empty desert down south. That’s where I would fight the authentic war—an oxymoron and common fantasy of weary warriors. Ed had already discovered his in those slickrock canyons. This man Ed had a deep fervor and humorous passion for defending the wilderness that I found attractive.

I believe Ed Abbey considered himself always a writer first. He was constantly scribbling stuff in his pocket notebook, stealing other people’s best jokes. By the early 1970s, it was clear he was working on something. I didn’t ask about it directly, but he started dropping hints.

Conversely, former Sergeant Peacock, a Special Forces medic, was a bit deranged in 1970, still looking for a noble war, and I seriously considered going back to Vietnam as a journalist. Though I spoke conversational Vietnamese, I needed to be able to read and write it. I scored a graduate fellowship in intensive Vietnamese at the East-West Center at the University of Hawaii and took a free trip to the islands, where I spent the bulk of my time exploring waterfalls and watching fish. While I was there, I heard that Ed’s wife, Judy, had died of leukemia. I wrote to him saying I was thinking of him. Ed wrote back asking me to come on up to Utah and we’d take a trip into the Escalante canyons.

As soon as I got back to the mainland, I met up with Ed in Kanab, and we slid east to the road up Cottonwood Canyon. South of Kodachrome Basin, we pulled off the rutted road onto a track leading to an old drilling site. The rig was gone, and the hole was capped, deserted but not abandoned. A lot of stuff was lying around; the workers would be coming back. Ed found a spanner, fit the wrench around the cap, and unscrewed it. We dropped a rock into the hole, then a chain and some other stuff—we heard only wind sounds whistling. I found a pile of used-up diamond drill bits. They all went down the hole. Ed grinned: “Should take them a while to drill through all that junk.”

We eventually made our way through a dendrite of immaculate narrow canyons down to Glen Canyon’s Lake Powell, the reservoir that the dam on the Colorado River had created between Arizona and Utah. That night, around a small campfire, Ed asked me if I knew anything about explosives. I said I had been field trained in simple demolitions in the Green Berets and had filled in for our demolition expert in Vietnam when he was wounded during the summer of 1967.

Hearing the manner in which Ed talked about Glen Canyon Dam—houseboats, explosives—I figured it would show up in the book he was writing, but I didn’t know how and I didn’t ask. Ed could be sensitive to criticism of his work. A mutual friend had read an early manuscript of what would become The Monkey Wrench Gang and had called it “a piece of shit”; that hurt Ed, and I didn’t want to join the league of unsolicited critics.

Ed and I saw a lot of each other in the early ’70s. We took a bunch of truck camping trips into the Cabeza Prieta, Dripping Springs Mountains, the Galiuro and Superstition Mountains. In the Superstition Wilderness Area, I snapped a photo of Ed sitting on a rock, writing in his notebook. Later, he asked me if he could use it on the back cover of his new book. In 1972, the two of us split a job (neither of us wanted full-time employment, so we could travel) as “custodians” of a large, private wildlife refuge in central Arizona on Aravaipa Creek. The job was nothing: All you needed to do was live there, keep a few horses rideable, and explore the country. In November, I caught a glimpse of what would be one of the last Mexican wolves in Arizona until 1998, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would reintroduce the lobo. I lasted almost a year at the job, Ed for part of another. Defenders of Wildlife eventually canned us both: me for insubordination, Ed for skinny-dipping.

It was during that winter in 1972 that Ed, a couple of friends, and I started taking out billboards and construction equipment; we plotted against coal mines, smelters, and the railroad bridges that led to them, and even the clear-cuts in the national forest system. I was unaware of any larger philosophical or political backdrop for our misbehavior but assumed it had something to do with Ed’s book. Ed was a prodigious researcher and had read up on demolitions and where you could legally buy ingredients for them. He studied the professional manuals on running and repairing bulldozers and other large earthmoving equipment. Ed wanted his book to read accurately to any engineer or bulldozer operator as well as to his friends. So, Ed and I, along with a few of our buddies, got out on the land and practiced, though as three- or four-person teams, we were often careless and close to recreational in our destructive verve. At any rate, the monkey-wrenching days had begun.

That said, we still had to make a living, and Ed gave me great job advice: “Douglas, you should apply to the National Park Service for seasonal work; they give you a quitting date to look forward to.”

Ed applied for fire-lookout jobs on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon and in Glacier National Park. I looked at a map of the West and picked a relatively new park: North Cascades. They offered me a job as a backcountry ranger, which I thought would suit me since I would live out of a backpack and sleep under the stars or in a tent (it could rain hard in the Pacific Northwest). But I missed something: Anarchists tend to make lousy law-enforcement agents, and I was no exception. In three summers of ranger work, I managed to write a single ticket on an illegally parked Winnebago. At the end, I left North Cascades for Glacier National Park in Montana, where I had taken up full-time filming of and advocacy for grizzly bears.

When the bears hibernated, I hightailed it down to the Southwest deserts. I rented a cheap place outside Tucson and looked up Ed. Both of us were unattached at the time, December 1973. By Christmas Eve, we found ourselves at a topless bar and tried to drown our snivels with cheap whiskey. Thinking it less piteous, we bolted for my pickup, loaded it up with beer and camping gear, and took off into the deep night driving due west.

We were heading for the Cabeza Prieta via the Tohono O’odham Nation Reservation, some 150 miles distant. It was a black night, and we slowly navigated the empty highway frequented by jackrabbits, coyotes, and javelinas. Several hours before daylight, we arrived at the summit of Charlie Bell Pass.

The road down off the pass into the Cabeza Prieta was terrible, and the federal Fish and Wildlife Service had rightly closed it. My pickup was old and two-wheel drive, but I had a high-lift jack in the back of the truck. We had been drinking beer most of the last 100 miles and had enough liquid courage to brave the steep route down.

Only about 300 feet down the treacherous, bedrock jeep trail, I high-centered the pickup and got stuck with the rear wheels spinning in the air. We jacked up the ass end of the truck and rocked it down the slope, regaining traction. We repeated this drill three more times before we reached the desert floor and level ground.

Ed and I continued north, around the end of the Granite Mountains, until we got stuck in the sand around daylight. We threw out our sleeping bags and crashed on the ground for a few hours. A day later, we followed old tire tracks into Eagle Tank, a water hole drilled by torrential monsoon rains, in the southern half of the Sierra Pinta. By New Year’s Eve, the weather had blown in, and it sleeted on us—a rare occurrence in the lower Sonoran Desert. Ed had bought a bunch of stuff at an army surplus store in Tucson for his research on the monkey-wrenching book, including a large camouflage net big enough to cover the pickup. We rigged up a tarp and built an ironwood fire below it. We squatted out of the rain for the day and talked. Ed shared his ideas and the details of his book project, and I finally knew what he was up to.

I also had, in the back of my truck, a small field library, including an early copy of the Special Operations Military Manual on improvised munitions, which I had liberated from the U.S. Army. It had recipes for rudimentary versions of napalm, thermite, and other explosives, and you could buy the ingredients at hardware stores and drugstores. I dug it out and gave it to Ed.

Eagle Tank was wild, empty country; there probably wasn’t another human for 50 miles. We got out our packs and started walking north, toward Sunday Pass, along the base of the Sierra Pinta. The mountain ranges out there were a half dozen parallel, sharp igneous ridges spread across nearly 100 miles, sticking up vertically a couple of thousand feet and drowning in their own detritus. The boundary between bedrock and desert sands was very abrupt.

At the foot of Sunday Pass, we noticed an ancient bighorn sheep skull, the corrugated horns unraveling with time. Just then, we both looked up; from far away, we could hear the thunk-thunk-thunk of helicopter blades. I raised my binoculars and spotted a Chinook flying over our camp and coming straight toward us, about a mile away. It was probably just running a routine drill, but we had failed to get a permit to be out here and didn’t want to explain. Luckily, the chopper hadn’t seen our vehicle; the camouflage net had worked.

Ed and I instinctively jumped off the rocky summit of the pass into the sand below and hid under a palo verde tree. We turned our faces away as the Chinook passed over and disappeared into the far valley.

We were both breathing heavily. Ed put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You’re shaking, Douglas.”

“I guess I still take this shit seriously,” I mumbled. “Those fuckers buzzing the wilderness just like the choppers they used to hose down on me in Vietnam.”

“What helicopter was that?” Ed asked.

“It was just one of our choppers, you know—those flyboys up there don’t care who they spray bullets down on. It’s just something to shoot at: water buffalo, Montagnard babies, Green Beret medics, all the same.”

I stood up and brushed the sand off. I was still trembling and said, “I believe helicopters for me might be evil incarnate. In ’Nam, they dealt death from the sky while answering to no one. The worst place for me to see them is in the wilderness. I’m a little crazy on this one, but I think I’d like to shoot them down.”

We returned to camp and built a fire. I had recovered somewhat from what I would later recognize as one of my “flashbacks,” but I was still shaken. Ed had been very kind and supportive. This was the soul of the man I grew to love. Edward Abbey owned a prodigious intelligence and could be quite intimidating. But not that day—he had been exceedingly gentle. Later that night, I asked him about The Monkey Wrench Gang, its theme of “no compromise in defense of the wilderness,” and what it was he really cared about.

“People,” he said, “people like you and our friends and families. I would never sell out a friend for an idea. A single brave deed is worth a hundred books, and this book will be no different.” Later, I would note—of great importance to me—that five years before it even had a proper name, Ed nailed post-traumatic stress disorder in the character of Hayduke with precision and depth.

The Monkey Wrench Gang was published on August 1, 1975, and at the end of that year, Ed and I squabbled. Hayduke was, in a lowbrow manner, famous: “Hayduke Lives” was scribbled on the bathroom walls of saloons throughout the American West. But George Washington Hayduke was also a dolt. The publisher’s legal staff had Ed write me an embarrassing letter saying to take only the good parts of Hayduke and forget the rest, etc.—that sort of litigious spit-dribbling disclaimer.

That winter, we were both in Moab, Utah, and we hiked upstream on Mill Creek to a junction where there was a boulder carved with petroglyphs, displaying a crude map of the drainage. Upon that rock, we burned the letter, and we never spoke of the origins of G.W. Hayduke again.

I can see that Ed probably did me a favor in creating a caricature of myself whose dim psyche I could penetrate when my own seemed off-limits; Ed painted the ex–Green Beret Hayduke with precise brushstrokes as caught in an emotional backwater, an eddy out of whose currents I wanted to swim. The only thing worse than reading your own press was becoming someone else’s fiction.

That road never quite ended except as they all do: Ed Abbey died the morning of March 14, 1989. My medical shift had started at midnight, so I was with him. He died of complications from pancreatitis. He also died as brave a death as I’ve attended. Since the medical profession misdiagnosed his condition for years, his final moments were not easy. The complication was portal hypertension.

Midday, three good friends and I packed him with dry ice, tucked him into a sleeping bag, and loaded him into the back of a pickup. We drove west, deep into the Cabeza Prieta (the last time Ed smiled was when I told him where he was going to be buried). We all took turns digging the grave, lying down in the hole to check out the view, and then planting Ed in his illegal home.

Ed’s grave is still there. I check in on it most every year. It’s intentionally not easy to find. Since I regard the place as a spiritual site, I don’t go there often, and then usually to leave offerings, like effigies of bears or clamshells.

Some years, I visit on March 16, my Day of the Dead: the anniversary of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam (I was 20 miles away when it happened) and also the day in 1989 when three friends and I buried Ed Abbey. One such year, I traveled alone and came bearing gifts, a bottle of mezcal and a bowl of pozole verde I had made. I sat quietly on the black volcanic rocks, listening to the desert silence, pouring mezcal over the grave and down my throat until the moon came up an hour or so before midnight. Suddenly, I heard a commotion to the south, the roar of basaltic scree thundering down the slope opposite me. A large solitary animal was headed my way.

I got the hell out of there.

Two days later, I told my story of the desert bighorn ram that I heard but never saw to my poet friend Jim Harrison.

“Well, Doug,” Jim said, “maybe it was old Ed.”

After a half century in print, The Monkey Wrench Gang comes at us most timely in 2025. Ed’s beloved, essential American wilderness has never been in greater peril. His habit of challenging authority hits the bull’s-eye in fighting today’s terrifying drift toward fascism and world war while living in a scorching era of accelerating biological extinctions.

Worldwide, the warming climate is banging at several tipping points, heralding lethal consequences. Yet we pretend we are not part of nature’s cycles. We ignore climate change at our peril; species evolve within a habitat and often don’t persist without the conditions of their genesis. This applies to all species, including humans. The highest average global temperature with Homo sapiens present was at least 1.5 degrees Celsius above baseline of preindustrial levels. We are currently at around 1.55 degrees Celsius above baseline, and many experts claim that number could reach 3 degrees by the end of the century. After that, it’s Russian roulette—no one knows what may happen; we’ve never been there.

Likewise, as Ed told us, our true home is the wilderness: For our first hundreds of thousands of years on Earth, human intelligence was carved in habitats whose remnants today we would call wilderness. Only in the past 12,000 years or so have we modified that wilderness, first with the late Pleistocene extinction and then with the rise of agriculture. Honed in that preagricultural landscape, our organic intellectual evolution owes little or nothing to our time on farms or in cities. That relationship is something I don’t want to gamble on—the indispensable fight to preserve wilderness is still our first line of defense.

Young people have the most to lose. It was Ed’s dream that small groups or cells of inspired activists would arise across the country. These are indeed the planet’s most dangerous times, and our opportunities to resist will require a fight; time to resist. We can all gather strength from Ed’s 50-year-old book.

As Ed remarked long ago, standing by that deserted drill hole in Utah, “Someone has to do it.” •

This essay is drawn from the introduction to a new edition of The Monkey Wrench Gang, by Edward Abbey, forthcoming from Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Author, disabled veteran, filmmaker, and naturalist Doug Peacock is the founder and president of Save the Yellowstone Grizzly. Peacock was a Green Beret medic in Vietnam and the real-life model for Edward Abbey’s George Washington Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang.

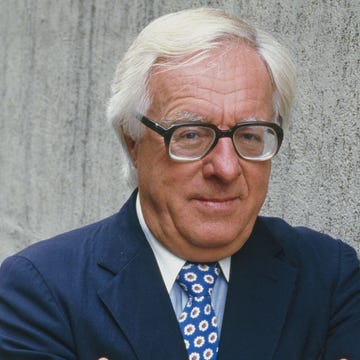

![<i>THE MONKEY WRENCH GANG [50TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION]</i>, BY EDWARD ABBEY <i>THE MONKEY WRENCH GANG [50TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION]</i>, BY EDWARD ABBEY](https://hips.hearstapps.com/vader-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/1748457630-monkey-wrench-gang-2000x1000-683757fd9c4ef.jpg?crop=0.394xw:0.984xh;0.295xw,0&resize=980:*)