The “forgotten lands” of California and the rest of the American West had a moment recently. A proposal by Utah senator Mike Lee to sell off huge swaths of public land as part of President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill put a klieg light on the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) domain. In California, that area encompasses 15 million acres of mostly wild, unoccupied terrain across the state—more than double the acreage of our nine national parks—from the Lost Coast in Northern California to the Mojave Desert in the south, plus nearly 2,700 miles of wild and scenic rivers from the Klamath to the Amargosa, amounting to just over 15 percent of the state.

With a pitched battle raging over the future of these public lands, Josh Jackson’s The Enduring Wild: A Journey into California’s Public Lands, a beautiful book of photographs, maps, and illustrations coupled with accounts of Jackson’s journeys of discovery to far-flung but public corners of California, is incredibly timely. Senator Lee’s proposal was struck from the budget bill because the Senate parliamentarian ruled it out of order and a rowdy coalition of MAGA-adjacent hunters and anglers raised a powerful ruckus in favor of keeping the land public. But Lee said he’s not done trying to off-load public property to private interests, which raises the awful question of how much of this enduring wild will, in fact, endure.

As Jackson explains, this vast estate is largely “forgotten” not only because the state’s national parks are more charismatic in comparison, but also because of the land’s history. This is land “no one else wanted.” Until now.

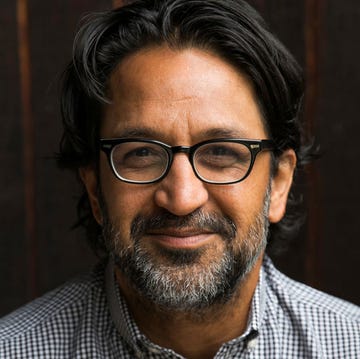

The author is on a mission to ensure that as much land as possible is kept public for as long as possible. He walked 381 miles on 32 trips across three and a half years, and in these pages, he is a companionable, clear-eyed guide to richly diverse landscapes from the Colorado River border with Arizona, through the Mojave and Bodie Hills east of the Sierra Nevada, to the Carrizo Plain in the Central Valley, through Berryessa north of the Bay Area, to the King Range on the far northern coast and the remote, nearly inaccessible wilderness along the Eel River.

The public lands of California are too varied and vast to be contained in one book, but The Enduring Wild is a compelling plea and an inspirational call to action to get to know these little-known but often-awe-inspiring places, which are now potentially on the auction block. Each chapter explores a particular place and offers a challenge to the author, and thus the reader: to slow down and observe, to be as contemplative as you would on a pilgrimage, to find your own kind of attachment to place, to give back in some form of reciprocity to the land and its inhabitants, and to protect these “leftover” BLM landscapes that “face the greatest risk of destruction.”

Jackson is an evangelist in the spirit of John Muir. But while Muir went to the mountains to find his holy land, the author finds holiness in the lowlands, foothills, valleys, and deserts, too. He doesn’t just preach to the choir. He goes deer hunting with friends, and although they come up empty, he explores the important contribution of hunter-conservationists to protecting public lands and the different kind of eye for the ecosystem that a hunter has versus a hiker. Jackson believes that people will protect what they know and love and that “everyone’s path to the outdoors is uniquely their own.” He is an “equal opportunity recreationist,” a phrase he borrows from one of the advocates for the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument.

Jackson also believes that our public lands could be common ground for a “radical center” in our increasingly polarized public life. Many of the campaigns to protect BLM lands by designating them as national conservation lands—categorized as national monuments, conservation areas, scenic areas, recreation areas, wild and scenic rivers, national trails, wilderness areas, and wilderness study areas—have, in fact, been successful because they have brought together people who might not otherwise share a campfire.

Hunters, hikers, ranchers, off-roaders, bird-watchers, botanists—it takes a broad coalition to protect public lands that supposedly no one wanted but some still covet for private gain.

I’ve been in and around enough conflicts over public lands in the West to be a bit of a skeptic when it comes to the broader potential of this radical center to heal our nation’s divides, but like Jackson, I’m still a true believer in a shared campfire on the public lands that belong to all of us.•

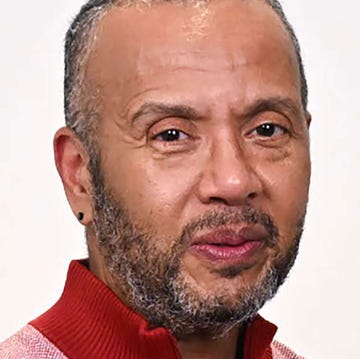

Jon Christensen is the director of the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies in UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.