Even if you didn’t know the fate of Noah Davis, one look at his ghostly painting of a solitary Black man hunched in a posture of resignation with one arm reaching out to grasp something that isn’t there and you might guess that his death was imminent. It is one of Davis’s last paintings, completed in 2015 several months before he died of cancer at age 32. The vertical background panels of mauve and gray, the crisp pale geometries of the sidewalk, display a sophistication and an awareness of art history—a nod to the spiritual abstraction of painter Barnett Newman—that offset the maudlin. It is a painting of complete surrender.

It seems doubtful that Davis, or any worthy artist, would want the details of death to overshadow his art. After all, Davis was just gaining stride in Los Angeles, where he’d moved in 2004 after studying at Cooper Union in New York, and showing with powerful galleries. Now the first international survey of his art, eponymously titled, concludes at the Hammer Museum, where it is currently presented by curators Aram Moshayedi and Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi. The exhibition will continue until August 31.

The uncluttered show presents about 50 works in total made between 2007 and 2015 that are aqueous and amorphous in parts, terse and exacting in others. Davis could bring us into the action of a picture like a soft-spoken person at a crowded party.

I met Davis only a few times, when he was working at the Art Catalogues bookstore in West Hollywood. Being surrounded by so much inquiry had an effect: The Hammer survey reveals Davis’s rigorous self-questioning about the function and purpose of art, those matters especially vexing for him in a world that was not entirely welcoming to Black artists. “Davis created a ‘missing link’ between art, himself and his community—an ‘alternative canon’, as he called it,” curator Paola Malavassi writes in the show’s catalog.

To address that very issue, in 2012, Davis and his wife, artist Karon Davis, opened the Underground Museum (the UM, as it came to be known) in a storefront in Arlington Heights, a largely Black and Latinx area of Los Angeles. Recognizing the intimidating nature of museums for most people, not just those of color, they installed a bar and seating for music, readings, and hanging out while showing work they considered urgent. The nonprofit’s mission statement was low-key radical: “Ultimately, I want to change the way people view art, the way people buy art, the way they make art. I’ve always tried to balance the tight rope of making my art accessible to those who are aware of the craft, and those who aren’t convinced of art or more specifically my artistic objective.”

In 2013, Davis curated the UM’s spunky show Imitation of Wealth by making copies of iconic art made by ’60s artists like Dan Flavin (fluorescent lighting), Jeff Koons (vacuum cleaners), and On Kawara (a lettered date, his father’s birthday, in white on black). Pieces from the exhibition are on view in the Hammer show.

Curator Helen Molesworth, who was a key early supporter of Davis and the UM, wrote that the show—titled after the Douglas Sirk film on hiding racial identity, Imitation of Life—drew attention to an unacknowledged problem: “It’s the museum and the market that have created the condition of scarcity around that object, meaning that the art world defaulted on the avant-garde’s original arrangement, which was more on the side of life and the everyday, than it was on the side of art.”

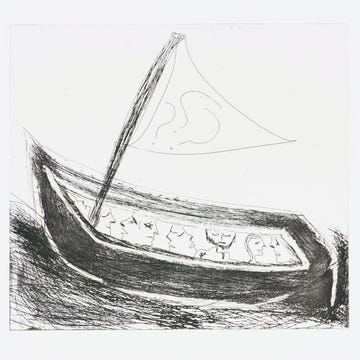

Notably, the success of the UM contributed to the acceleration of his fame as a painter, even as his illness progressed. It also corresponded with a surge of popularity in figurative art over the past two decades. Since the early 2000s, Davis had gone to flea markets to find vintage photographs of Black life, anonymous snapshots that he posted on a website he’d started with his filmmaker brother, Kahlil Joseph, called FEB MAG. He used them as source material in his early paintings, some with slightly mystical moments: a man riding a unicorn, a mother and child in a living room, a spray of glitter coming from the open door of a bedroom. In a 2011 lecture at the Corcoran School of Art & Design, he explained, “I wanted to create narratives that are…almost like a Fellini.” They may be about love or about death, “but I want it to be more magical. I don’t want it to be so stuck in reality.”

Using acrylic or oil on canvas, he combined thin washes with thick layers of paint to emphasize the outlines of his drawn figures. As he told Dazed interviewer Ben Ferguson in 2010, “race plays a role in as far as my figures are Black.… If I’m making any statement, it’s to just show Black people in normal scenarios, where drugs and guns are nothing to do with it.”

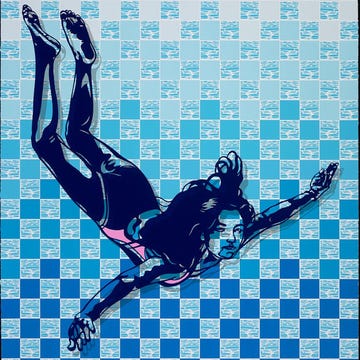

These include scenes of family life, of people swimming, resting, enjoying activities of leisure. A 2013 series of paintings titled 1975 are based on pictures taken by his mother in that year and discovered on an undeveloped roll of film found by his brother in their late father’s house. In painting the pictures, Davis was seeing through his mother’s eyes.

Though he’s a native of Seattle, Davis’s work is recognizably of Los Angeles. Most obviously, this can be seen in the paintings that incorporate the work of Paul Revere Williams, the Black architect who designed some of the city’s most exceptional buildings, including part of the Beverly Hills Hotel, where he was not allowed to dine because of whites-only policies. The connection was personal: The artist’s father, Keven Davis, an attorney who represented tennis superstars Serena and Venus Williams, had been close friends, even fraternity brothers, with the architect’s grandson. Davis’s 2009 painting The Architect is based on a photograph of Williams posing before a model of a building. Though painted mostly in grays and blacks, a splash of watery white drips over the face. His features are literally whitewashed.

The study culminates in the 2014 series of paintings of Pueblo del Rio, the 1942 white-walled modernist housing project in Central-Alameda designed in part by Williams to provide efficient and affordable living in a working-class, largely Black neighborhood. The area and buildings later devolved into violence and poverty, but Davis paints Pueblo del Rio with classical ballerinas and uniformed musicians performing on the wide green lawn, seemingly returning the area to its more optimistic past. In this work, Davis pays homage to the influential Black artist of a previous generation, Kerry James Marshall, and his paintings of another Williams project, Nickerson Gardens. The older artist also chose to normalize scenes of Black life, such as relaxing by a lake, dancing, or chatting in the beauty parlor.

So many of Davis’s late paintings are made as though he’s seeing everything as a miracle of the moment. These are not big statements but scenes of simple pleasures: a seated man reading a newspaper, two young women collapsed in rest on a beige sofa.

The latest work is manifestly concerned with death: people standing around a coffin about to be lowered into the ground or a man reclining in an arcadian green space but leaning on an elbow to stare at us, the viewers. As his cancer progressed past all hope, the Davises moved to Ojai with their son, Moses. From his sickbed, Noah organized several years’ worth of shows to take place at the UM, the last being videos by Rodney McMillian in 2020. The UM is now closed.

One last request was for Karon to take care of his “babies,” meaning the hundreds of paintings that he was leaving behind. In planning the Hammer show, she reexperienced their personal history and intimacy. She also designed the simple bronze colored seating that is intentionally placed in the museum’s galleries. It invites an extended viewing of this profoundly moving exhibition.•

Noah Davis

Until August 31, 2025

Hammer Museum

10899 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, the author of Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s and Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O’Keeffe, has written numerous books and articles on modern and contemporary art with an emphasis on California and the West. They can be found at hunterdrohojowska-philp.com.