On Monday, April 8, the earth, moon, and sun will align, and the moon will cast a shadow over the earth for four minutes and 28 seconds in some areas, an alignment of heavenly bodies that won’t happen again in North America for another 20 years. The eclipse will be the second seen in the western continental United States in the past 7 years and is prompting thousands of people to flock to the path of totality for arts events, parties, lectures, concerts, and healing ceremonies.

This essay was adapted from the Alta Weekly Newsletter, delivered every Thursday. To keep reading, become an Alta Journal member for as little as $3 a month.

SIGN UP

Two Delta Airlines flights will take off from Austin and fly to Detroit along the path of totality for ticket holders to experience it from the air. On the ground in Texas, where astronomers say there will be a 50-50 chance of clear visibility, eclipse chasers are paying sky-high airfares and hotel rates to get to this moment of totality. The Reveille Peak Ranch in Burnet, Texas, expects more than 30,000 visitors for the Total Eclipse Festival, featuring six music stages, an immersive art installation by Meow Wolf, and a “multiversal dome” projecting art and music created by Chroma, a tech studio from the founders who designed the Sphere in Las Vegas. The event will also feature a gathering of “Neo-Shamans” from Guatemala who want to adapt their ancient knowledge and rituals for the 21st century and Dr. Andrew Weil lecturing on how total solar eclipses affect human psychology. During the totality, there will be a collective meditation around a bonfire.

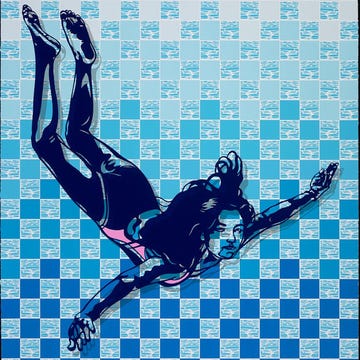

In Austin, Vampire Weekend is playing an eclipse show at the Moody Amphitheater, and southwest in the Hill Country town of Kyle, artist Eames Demetrios will unveil a monument to the eclipse at an event space called the Plant.

Mazatlán, which sits on the outskirts of historically Aztec territory on the west coast of Mexico, is hosting the Portal Festival, which offers up four days of “consciousness and spiritual growth,” with international DJs, workshops, and scientific lectures, all set in an eco-village that will be built along the path of totality. Edward Krupp, the director of Los Angeles’s Griffith Observatory, will be on hand to lecture on astronomy and Mexican culture.

Krupp, an internationally recognized expert in archaeoastronomy, studies how ancient cultures viewed the sky. He says that the Aztecs wrote extensively about astronomy and eclipses in their codices, translated by Spanish priests who came to Mexico in the 16th century. For the ancients, Krupp explains, eclipses were not a spectacle to celebrate. “They were trouble,” he says. “Fundamentally, they meant that everything was going to be unstable.”

“We have evidence that when an eclipse occurred, people would lament, go out in the streets, and hide their children, lest, as it said, they’d be turned into mice,” he says.

Other cultures have their own takes. Eclipse comes from the Greek word ekleipsis, meaning “an omission” or “an abandonment”—basically, the sun abandoning us to darkness. The western Navajo believe that during an eclipse, the sun and moon were making love.

“Some cultures believe you shouldn’t look because it would be like watching your grandparents [have sex],” says Vivian White, an educator with the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. For White, the spectacle is deeply life-changing, both scientifically and spiritually. “Being in the shadow of the moon is second only to childbirth or being at someone’s death,” she adds.

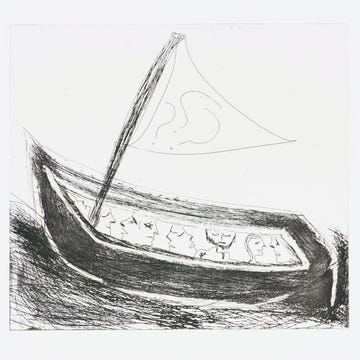

Hebrew interpretations of the book of Genesis have stated that an eclipse occurred on the day the animals boarded Noah’s ark. The Dresden Codex, a Maya hieroglyphic divinatory almanac, hints at the idea that the Maya believed that something was eating the moon. Miwok people living near present-day San Francisco and Sacramento saw eclipses as signs of the continual struggle for power between the sun and the moon. At the beginning of an eclipse, the Tipai people of Southern California began a ceremony intended to dispel its harmful effects.

Because the ancients depended on the sun to order the cycles of day and night and the seasons, an eclipse represented a vital disruption to the world’s very existence. As science has advanced, eclipses have become relatively easy to predict and essential for scientific discovery. Because it’s one of the only times the sun’s corona becomes visible, analyzing the light around an eclipse has also helped scientists determine its composition. During a solar eclipse in 1868, French astronomer Jules Janssen and English astronomer Joseph Norman Lockyer observed a yellow line in the corona, later identified as helium’s spectral signature. During April 2024’s eclipse, a radio telescope in California will try to use the moon as a shield to measure emissions from individual sunspots.

Only the earth has a moon that is precisely the right size, and at the right distance, to align for a total solar eclipse. This coincidence is especially unusual because the moon is about 400 times smaller than the sun while also being 400 times closer to us. When these two celestial bodies align, they will briefly appear the same size.

“I once heard that seeing the totality would make a religious person become an atheist and an atheist become religious,” says Tiffany Shlain, an artist and a filmmaker who plans to watch from the Plant. “Will I be changed? Who knows. But I’m determined to experience this totality firsthand.”•

Correction: This story was updated on April 4, 2024 to clarify that the moon will cast a shadow over the earth during the total eclipse.

Rachel Lehmann-Haupt is an award-winning journalist and author who lives in Sausalito, California.